2019.7.7This was our last day in the Faroe Islands. The plan was to take a ferry to Mykines Island. When we first made our itinerary, I hadn’t paid much attention to the ferry schedule. Only when booking the tickets did I realize that this was the only day with any availability left. Had we waited any longer, we might not have been able to go at all.

The ferry departs from the town of Sørvágur on Vágar Island, which is very close to the airport. We had stopped there for some shopping on our first day in the Faroes.

As soon as we exited the fjord, we saw the arch-shaped Drangarnir islet and the triangular peak of Tindhólmur. Just days earlier, we had only seen them from afar across the fjord, but now, from the boat, we were up close – the ferry passed right between the two islands. After several days of cloudy skies, we were finally treated to a beautiful day of blue skies and scattered white clouds.

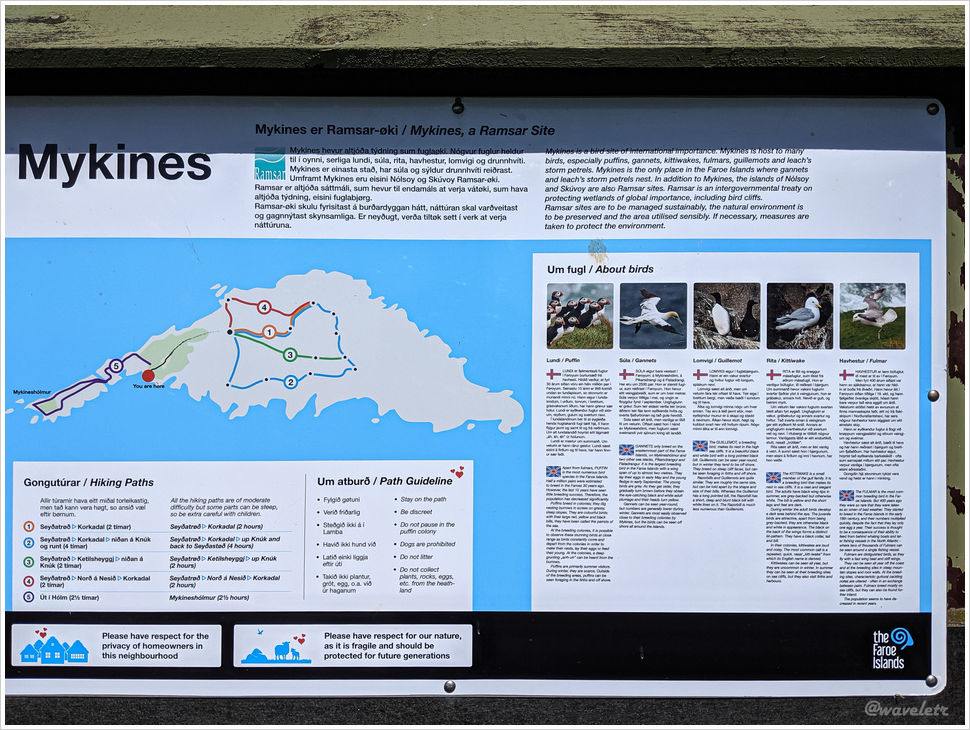

Mykines is the westernmost island of the Faroe Islands, and it takes about 50 minutes to reach it by ferry. The island is roughly triangular in shape, with its westernmost tip extending into a small islet about one kilometer long. Though technically separated from the main island, it’s connected by a narrow footbridge. Mykines is home to large colonies of seabirds, most famously puffins. Most visitors come specifically to cross the bridge to the western islet to see the birds. Unless staying overnight, there’s usually not enough time to explore the vast eastern side of the island.

Climbing up a small hill, we soon came across a modest memorial built along the ridge. It was erected in 1930 to honor the islanders who lost their lives at sea. As is common on the islands, there were plenty of free-roaming goats nearby. One of them kept repeatedly butting its head into the ground, perhaps a territorial behavior.

In the distance, we could already see the lighthouse at the far western tip of the islet. A group of hikers making their way along the trail toward it.

We began spotting puffins here and there. They have a stout build and are actually smaller than I had imagined. Their large, brightly colored beaks, disproportionate to their bodies, give them a slightly comical appearance, which is probably why they’re so beloved. The puffins here are Atlantic Puffins, found along the coasts and islands of Northern Europe and northeastern Canada. They belong to a different subspecies than those found in Alaska.

To cross the bridge, we had to descend from the ridge to the lower slopes. This is an area filled with puffin nests. Puffins are social birds that prefer to nest in colonies, building their burrows in the grassy cliffs near the sea. They fly out over the ocean to catch small fish and crustaceans. Before taking off, puffins are extremely cautious, often standing at the mouth of their burrows for a long time, scanning the surroundings. At the slightest disturbance, they retreat back inside.

On the hillside, the puffins tend to leave for feeding around the same time. Just as we were about to head down, a ranger stopped us on the trail, explaining that we needed to wait about 20 minutes to allow the local puffin colony to safely head out to sea.

This is the bridge that connects Mykines to the narrow islet at its western tip. The surrounding cliffs are home to large numbers of kittiwakes, a type of small gull that resembles pigeons at first glance. Many of them perch in pairs. Unlike puffins, which nest in burrows on grassy slopes, kittiwakes build their nests directly on the steep cliff faces, often on ledges barely wide enough to hold two birds.

After crossing the footbridge, we began climbing up the ridge again. Here, we started to see many Northern Gannets, which nest along the north-facing cliffs. Different bird species seem to occupy their own distinct territories, coexisting without much interference. Adult Northern Gannets have an impressive wingspan, up to 1.8 meters, and they rely mostly on gliding for flight. They are the largest seabirds in the North Atlantic.

Despite their large size, the nesting space on the cliffs is surprisingly limited, and many gannets crowd together in tight colonies. Taking off is relatively easy. They simply leap off the edge and glide into the air. Landing, however, is a different story. Gannets often come in at near full speed, flapping their wings furiously to slow down while thrusting both legs forward, aiming for a tiny patch of grass beside their nest. It’s not uncommon to see them misjudge the landing and end up face-planting into the dirt, an awkward, if slightly comical, scene.

Northern Gannets form monogamous pairs and remain faithful for life unless one partner dies. Each year, the pair raises their chicks together, which is why you can often capture many intimate photos of male and female birds close and caring for one another.

Looking back from here, you can see the entire western side of Mykines. To the north, steep, layered cliffs rise almost vertically. This is where most of the Northern Gannets nest. The southern side is comparatively gentler in slope, and it’s primarily on this side that the puffins are active.

I didn’t continue all the way to the lighthouse and instead turned back here. Passing through the puffin colony, We saw more of these charming birds. Puffins with their beaks full of small fish are an iconic sight, but sometimes they carry a blade of grass or a wildflower, almost as if bringing a gift to their beloved.

When we returned to the harbor, there was still over an hour before the ferry return. The town is small, only about twenty or so buildings, mostly likely catering to the few overnight visitors. According to 2018 statistics, the island had just 10 residents. Near the harbor, there’s a café where waiting passengers gather to rest. Although the ferry was 40 minutes late, everything went smoothly, and we had a safe trip back.

When we planned our trip, we didn’t really know the road conditions in the Faroe Islands. Worried that getting to the airport from Tórshavn the next day might be too far, we booked a night’s stay in Miðvágur. However, upon arrival, the accommodations there were nowhere near as comfortable as the apartment we had in Tórshavn. Since we still had that apartment reserved for another night, we decided to return to Tórshavn. Fortunately, we were able to retrieve the keys from the owner’s locker and spent our final night there.

In the evening, we had dinner at Áarstova, a traditional restaurant in the city center. Afterwards, we took a stroll along the harbor before ending the night with a relaxed drink at a pub called Mikkeller. From our experience, in such a remote place, it’s best to stick to European-style restaurants. Trying Asian cuisine often leads to disappointment. Of course, that was our experience back in 2019; with more tourists now, things may have improved since then.

The next day, we flew out of the Faroe Islands, heading back to Iceland. Shortly after takeoff, to our surprise, we spotted the Múlafossur waterfall plunging into the sea from the plane window, a perfect farewell to our brief journey at the edge of the world.